Embroidered Hanging, 160 x 158.8 cm; late 14th century, Germany (currently held at the MET)

Embroidery is unlike other forms of textile decorations, because it is added after the fabric is taken off the loom and can be taken out later or added at any time so long as the fabric is stable. Historically, embroidery has been a craft mostly associated with women, and as such it has often been overlooked by scholars. The origins of embroidery are less known though, since textiles tend to deteriorate over time and embroidery is believed to be exceptionally old. What scholars do agree on is that embroidery was likely invented separately by different cultures in different times, revealing how instinctive the craft is to the human mind and body. A considerable amount of Medieval European embroidery examples do survive though, particularly Anglo-Saxon and Viking examples, which attests to the prominence of embroidery between the 6th and 16th centuries. During this time, many embroiderers, especially women, used the craft as a form of devotion, as a means of fostering a relationship with God, and as a way of providing spiritual guidance outside of church services.

Medieval Embroidery

Unlike today, textiles in the Middle Ages were highly prized and cherished especially ones with heavy ornamentation. Pearls, gems, precious and semi-precious stones, enamels, and cameos were all added to embroidery work as a form of visual enrichment in the Middle Ages. By the high Medieval period threads wrapped in thin gold or other metals were also incorporated into embroidery practices to add shine and luxury to textile works. In the Middle Ages, the practice of embroidery involved attaching fabric to a wood frame and stretching it tight. Embroiderers would then use needles made of wood instead of metal, for its affordability.

Embroidery ornamentations were almost exclusively reserved for the wealthy and the liturgy, although secular embroidery increased in the late Medieval period into the 17th century. The most prominent places for producing embroidery in the Middle Ages was France, Italy, and of course England where Opus Anglicanum is from. At this time embroiderers could be women or men, although embroidery was exclusively reserved for women in church settings by the late Medieval period. Embroidery designs could be influenced by patrons, abbesses, design artists, or the embroiderers themselves, it really depended on the work.

Horae secundum usum romanum illuminated manuscript, 15th century, France (currently held in the Département des Manuscrits, Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Opus Anglicanum

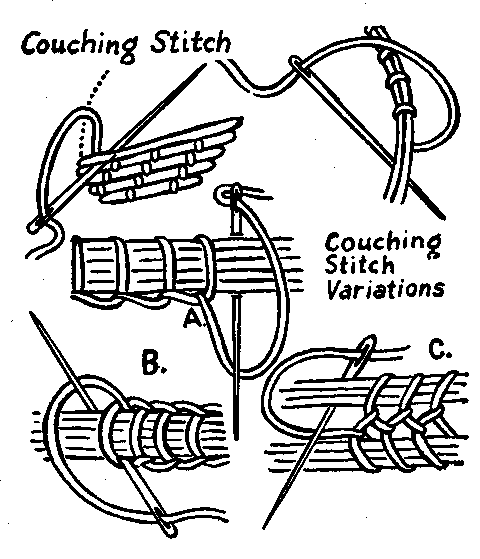

Opus Anglicanum, which is Latin for “English work,” is defined by its typical use of laid and couched work, stem stitch, and outline stitch. Opus Anglicanum is also characterised by tight stitches with clean back sides, gold threads, and detailed scenes. This English style of embroidery began in the Anglo-Saxon period as early as the 8th century and continued until the end of the Middle Ages and was exclusively done in guilds or workshops at the time.

Detail. Embroidered cross bellow collar of child’s tunic, 4th to 10th century, Egypt (currently at Dumbarton Oaks)

Early Middle Ages

Before the 12th century, wall hangings and furniture decorations were the more popular form of embroidered textiles, while the 12th century and onwards saw a popularity in decorated garments and accessories instead. Byzantine embroideries from the 4th century and onwards, were incredibly popular in Medieval Europe and the Christian world. Many of these textiles were sent to the west as diplomatic gifts and featured religious imagery. Early Christian embroideries from before the 10th century feature various designs which allude to Christ without needing to display God directly. This included imagery of the fish, vines, crosses, and ancient gods, a practice brought over from the days when Christianity was illegal. This practice would become less popular by the high Middle Ages, but this early style can be seen in the image on the right. Guilds and workshops existed as early as commissioned embroidery works became common (before the 10th century), but up until the 11th century embroidery was also an incredibly popular pastime for people.

High-Late Middle Ages

From the 12th century onwards, Medieval embroidery was marked by the increased used of luxury fabrics including silks, velvet, and damask. The later Middle Ages also saw an increase used of gold or silver threads and beading which added to the overall ornate look defined in this period. As embroidered secular garments and accessories became more popular in the high Middle Ages though, liturgical vestments continued to be given the most luxurious detailing and lavish ornaments as a form of visual hierarchy. So much gold and gemstones were used in liturgical vestments by the 14th century, that there are several accounts of people burning whole chasubles to extract the metal and stones. Opus Anglicanum became incredibly popular across Europe between the 12th and 14th centuries. Vatican inventory records from the 14th century, cite 114 works of Opus Anglicanum. The prevalence of Opus Anglicanum at this time, can be seen today through the vast number of extant examples recovered from all across Europe.

Detail. Butler-Bowdon Cope, 1335-1345, England (currently held at the V&A)

Detail. The Bayeux Tapestry (section 46-47), 11th century, England (currently held at the Bayeux Museum)

Many manuscript designs inspired contemporary embroidery, because artist sketchbooks could be used by embroiderers and manuscript workers which can account for similarities in later Medieval embroideries and manuscripts. The Pepysian Sketchbook from the 14th century features many sketches that resemble embroidery work from the same time, suggesting that this one book was used by various designers. Popular embroidery imagery included birds and other animals, flowers and plant motifs, abstract repeat patterns, historic or biblical figures and/or scenes, geometric shapes, and Latin/Greek writing. Although these characteristics stay somewhat the same over the Medieval period, the materials, techniques, and tools used to make embroidery changed drastically between the 6th and 16th centuries.

Imagery

Detail of birds. Pienza Cope, 14th century, England

Detail of birds. Pepysian Sketchbook, late 14th century, England (currently held at Magdalene College, Cambridge)

Tristan Embroidery, 232 x 402 x 2.5 cm, 13th to 14th century, Germany (currently held at the Gothic majuscule Museum, Kloster Wienhausen)

Detail. An embroidery design book, 1559, Italy (currently held at the V&A)

Recent scholarship, particularly from women, has sparked a new interested in Medieval embroidery objects as works of art defined by the female perspective and female devotion to God. The Tristan Embroidery is a great example of this, as recent research has suggested that Medieval nuns possibly had access to embroidery design books and would have shared them with different convents particularly in the Wienhausen region of Germany. This is believed because the Tristan Embroidery shares similarities with several other embroidery works made in the Wienhausen region, and through an understanding of how Medieval embroidery works scholars were able to understand that these designs use stitch styles that were too similar to be a coincidence.

Nuns and Convents

Nuns and convents were most famous in the Middle Ages for their embroidery works, as compared to laywomen. Many documents from this time, remark on the wonderful work of embroidery by nuns and abbesses and the prevalence of the practice in convents. In particular, convents were known to work on liturgical vestments for bishops, popes, and local churches. Christina of Markyate, a nun in the 11th century, is recorded as having given pope Adrian IV an embroidered mitres and sandals, which were the only gifts accepted by the pope due to their clear devotion and piety. At this time, works of this kind were typically regarded as secular and vain, but if it was done by ecclesiastical women it’s connection to vanity was seen as a repercussion of their devotion to God. Thus, Medieval nuns were praised for their embroidery work more than secular women.

Sophia, Hadewigis, and Lucardis, Altar cloth from the convent of Altenberg displaying The Adoration of the Magi, 125 × 390 cm, 14th century, Germany (currently at the MET)

Nuns often produced embroidery works that also served as advertisements for their convent. This also serves as evidence of women’s ability to contribute visual imagery to ceremonial places in Medieval Europe. Liturgical women were often tasked with decorating local churches as a way for nuns to keep busy, but this gave some power to these women over the visual imagery used within these spaces. The nuns at the convent of Altenberg for instance, produced intricate works of white-on-white embroidery, including the depiction of The Adoration of the Magi shown in the centre of the slide. This embroidery work was used as an altar cloth by the local church, but it also shows significant connections to the convent as the white-on-white technique can be connected back to the nuns of Altenberg nicknamed the “white canons.” St. Elizabeth of Altenberg died in 1231 and was canonized in 1235. Emperor Frederick II crowned her separated head, with her three children in attendance. The nuns of the convent at Altenberg eventually added St Elizabeth into one of their works displayed in the public church as a way of reminding viewers in the 14th century of the saint and her connection to the convent.

Secular Women

Although there are less surviving examples of secular-made embroidery works, we do know that secular women were encouraged to make their own craft works for the good of God. Embroidered objects were used in ceremonies of various types, including liturgical use, in ecclesiastical services, as burial dresses, or for the protection of lay people. When Matilda, Queen to William the Conqueror, died in 1083 she bequeathed “the chasuble which is being embroidered at Winchester by Alderet’s wife.” It is interesting to note that she specifies that the wife was the one embroidering this highly valuable project. In the story Erec et Enide a quote describes an embroidered liturgical vestment, gifted by a noble women. This story clearly shows how noble women at this time were expected to donate textiles to the Church, and embroidered works were considered valuable donations. Noble women were expected to work on ecclesiastical projects for donations, as a way of showing their obedience and their virtuosity as members of the nobility.

“Through a clever scheme, Guenevere, wife of the powerful King Arthur, got [the embroidered fabric] through Emperor Gassa. She had a chasuble made from it, and had kept it in her chapel for a long time, for it was good and beautiful.”

Erec et Enide (1170)

Embroidery Works

Reliquaries

Reliquaries are objects, either statues, decorated boxes, textile fragments, or various other art objects that hold relics. Either way these objects often took on holy properties themselves, as objects that have touched and held holy relics. The embroidered lid of the Arca de San Isidoro was done in a freestyle embroidery, a testament to the religious and meditative experience of embroidering, where the artist allowed the design to come together in the moment. This embroidered textile was likely done by pious women in Spain and then attached to the lid of the reliquary later.

Liturgical Vestments

Many examples of Medieval embroidery that still exist today, are often liturgical vestments since these were considered important art objects as parts of religious/ceremonial uniforms. Despite many liturgical vestments being destroyed for their ornate beading, the ones that were not destroyed were especially taken care of and thus have lasted into the 21st century. In contrast, secular textiles were often used until they wore down and disintegrated so the only examples of these that exist today have mostly been found in tombs (with a few exceptions, including the 14th century bra found in the floor of an Austrian castle).

Secular Clothing

Prior to the 11th century it was more common for secular people to embroider on their clothes themselves, and some scholars believe this practice could have been used to place the mind in a religious-meditative state to help them contemplate God or to embroider the magic of God into the garments. Embroidery was often used in the early Medieval/late Antiquity periods as a form of a magical and religious craft. These textiles are a further testament to the powerful use of embroidery in clothing by secular individuals prior to the 11th century, where symbols of God embroidered into one’s clothing allowed God to be with them at all times. Women as makers were often the ones who did this work for loved ones.

Statues and Altar Clothes

Churches were decorated with an abundance of textiles during the Middle Ages, often made by women and/or commissioned by patrons, both male and female. Statues in churches could be dressed in the Middle Ages as a part of a ceremony or special holiday. These costumes were often embroidered and made by women, and provided a mother-like experience of dressing small dolls. Next to liturgical vestments, altar clothes were the second most popular embroidered objects donated to churches.

Wall Hangings

Embroidered wall hangings in homes were particularly popular in antiquity and into the Middle Ages. These were often used to display religious devotion outside of formal religious spaces and could even be used as a meditative object similar to Renaissance prayer diptychs. Wall hangings were also popular in churches as a form of religious decorations, often produced by nuns in nearby convents. The practice of making was considered a meditative and psychedelic experience from working with small, detailed designs of religious themes.

Embroidery lining the lid of the reliquary of San Isidoro, 11th century, Spain (currently held at the Museo de la Real Colegiata de San Isidoro, León)

Conclusion

Up until the 13th century, women were encouraged to embroider but to only work on pious and religious works rather than purses or personal designs. This would later change as more secular embroidery works became popular and Protestantism began to diminish the sway of the Catholic church on people. As guilds and workshops became more prominent in the late Middle Ages too, tapestry weaving became more popular than embroidery as wall hangings became common home décor and tapestries had a faster output time. Convents continued to produce embroidery works, but at a reduced capacity, and as the Protestant reforms removed many of the convents from Europe. Embroidery work is still done as a craft practice to this day, and it continues to have a strong connection to women and feminist history.

Chasuble, 129.5 x 76.2 cm, 1330-1350, England (currently held at the MET)

Flavie Deveaux

Bibliography: Alain Mariaux, Pierre. “Women in the Making: Early Medieval Signatures and Artists’ Portraits (9th to 12th C.).” Women and Work in Premodern Europe: Experiences, Relationships and Cultural Representation, c. 1100-1800. Edited by Merridee L. Bailey, Tania M. Colwell, and Julie Hotchin. New York: Routledge (2018): 393-427; Budny, Mildred, and Dominic Tweddle. “The Early Medieval Textiles at Maaseik, Belgium.” The Antiquaries Journal 65, No. 2 (1985): 353-89; Bynum, Caroline W. “‘Crowned with Many Crowns’ Nuns and Their Statues in Late-Medieval Wienhausen.” The Catholic Historical Review 101, No. 1 (2015): 18-40; Cabrera Lafuente, Ana. “Chapter 4 Textiles from the Museum of San Isidoro (León): New Evidence for Re-Evaluating Their Chronology and Provenance.” The Medieval Iberian Treasury in the Context of Cultural Interchange. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill (2020): 81-117; Calendar of the liberate rolls preserved in the Public Record Office: Henry III, 1226-1272. Great Britain: Public Record Office, 1934; Campagnol, Isabella. Forbidden Fashions: Invisible Luxuries in Early Venetian Convents. Texas Tech University Press, 2014; Feliciano, María Judith. “Chapter 5 Sovereign, Saint, and City: Honor and Reuse of Textiles in the Treasury of San Isidoro (León).” The Medieval Iberian Treasury in the Context of Cultural Interchange. The Netherlands: Brill, 2020; Flury-Lemberg, Mechthild. “The Restoration of the Antependium of the Musee Paul Dupuy in Toulouse.” The Conservation of Tapestries and Embroideries. Getty Conservation Institute (1989): 11-15; Gajewski, Alexandra and Stefanie Seeberg. “Having Her Hand in It? Elite Women as ‘Makers’ of Textile Art in the Middle Ages.” Journal of Medieval History 42, No. 1 (2016): 26-50; Gourlay, Kristina E. “The Malterer Embroidery Re-Examined.” Young Medieval Women. New York : St. Martin’s Press (1999): 69-102; Kinoshita, Sharon. “Almeria Silk and the French Feudal Imaginary.” Medieval Fabrications Dress, Textiles, Cloth Work, and Other Cultural Imaginings. Edited by E. Jane Burns, Palgrave Publishing (2004): 165-176; Labarge, Margaret Wade. “Stitches in Time: Medieval Embroidery in its Social Setting.” Florilegium 16, No. 1 (1999): 77-96; Lee, Christina. “Embroidered Narratives.” Feminist Approaches to Early Medieval English Studies. Edited by R. Norris, R. Stephenson, & R.R Trilling, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press (2023): 54-82; Lewis, Katherine J., Noël James Menuge, and Kim M. Phillips. Young Medieval Women. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1999; Maguire, Henry. “Garments Pleasing to God: The Significance of Domestic Textile Designs in the Early Byzantine Period.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 44 (1990): 215-24; Ní Ghrádaigh, Jenifer. “Mere Embroiderers? Women and Art in Early Medieval Ireland.” Women and Work in Premodern Europe: Experiences, Relationships and Cultural Representation, c. 1100-1800. Edited by Merridee L. Bailey, Tania M. Colwell, and Julie Hotchin. New York: Routledge (2018): 93-128; Seeberg, Stefanie. “Women as Makers of Church Decoration: Illustrated Textiles at the Monasteries of Altenberg/Lahn, Ruppertsberg, and Heiningen (13th-14th. C.).” Women and Work in Premodern Europe: Experiences, Relationships and Cultural Representation, c. 1100-1800. Edited by Merridee L. Bailey, Tania M. Colwell, and Julie Hotchin. New York: Routledge (2018): 355-391; Staniland, Kay. Medieval Craftsmen: Embroiderers. University of Toronto Press, 1991; Thompson, Nancy M. and Anne F. Harris. Medieval Art 250-1450: Matter, Making, and Meaning. New York: Oxford University Press, 2022; Tibbetts Schulenburg, Jane. “Chapter Five. Holy Women And The Needle Arts: Piety, Devotion, And Stitching The Sacred, Ca. 500–1150.” Negotiating Community and Difference in Medieval Europe: Gender, Power, Patronage and the Authority of Religion in Latin Christendom. The Netherlands: Brill, 2009; Wyld, Helen. “The Gideon Tapestries at Hardwick Hall.” West 86th 19, No. 2, Chicago University Press, 2012; Young, Bonnie. “Needlework by Nuns.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 28, No. 6 (February, 1970): 263-277; Young, Bonnie. “Opus Anglicanum.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 29, No. 7 (1971): 291-298; Zeilinger, Dana. “Golden Threads & Silken Gardens 14th Century English Medieval Embroidery (Opus Anglicanum).” ProQuest, 2001.

check out More on the Topic…

Tanya Bentham. Bayeux Stitch. The Crowood Press, 2022.

Kay Staniland. Medieval Craftsmen: Embroiderers. University of Toronto Press, 1991.